The European Yew, Taxus baccata, is one of only three native British conifers (along with Scots pine and juniper). The trees can grow up to 28m in height, and have a spreading, rounded or pyramidal canopy. The leaves are evergreen, arranged spirally, but are twisted into two ranks, so that they appear alternate. Trees are of two sexes (dioecious), but sometimes branches change sex, producing ‘flowers’ of the opposite sex. Of course, in a conifer the sexual organs are in cones, not flowers, but the female’s seeds are surrounded by fleshy arils which superficially resemble berries (Figure 1). These arils are thought to arise from swelling of the axis immediately beneath the ovule, although Dörken et al., (2019) argue that they are highly modified strongly swollen leaves. Male plants bear globose male cones (Figure 2) which burst open to shed their pollen in early spring.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Yew is native to the British Isles. In Britain, Taxus baccata woodlands are mostly confined to the chalk of the South and North Downs in south-east England and also limestones in County Durham and around Morecambe Bay in Cumbria (Brzeziecki and Kienast, 1994, Thomas and Polwart, 2003). Individual yew trees are more widespread, occurring on a wider range of soils, especially on neutral to alkaline soils in the Peak District and Lake District. Since yew seeds germinate readily, and the trees also clone themselves vegetatively, it is often impossible to tell whether they are native or planted or the descendants of planting and it is uncertain whether the species occurs naturally in Scotland. In Britain, yew woods occur primarily on south- and east-facing slopes, and on sunny, windy, west-facing slopes. It likes mild winters, high humidity/mists and lots of rain (Tittensor, 1980) and does not thrive in areas with cold winters, bitter winds or salt spray.

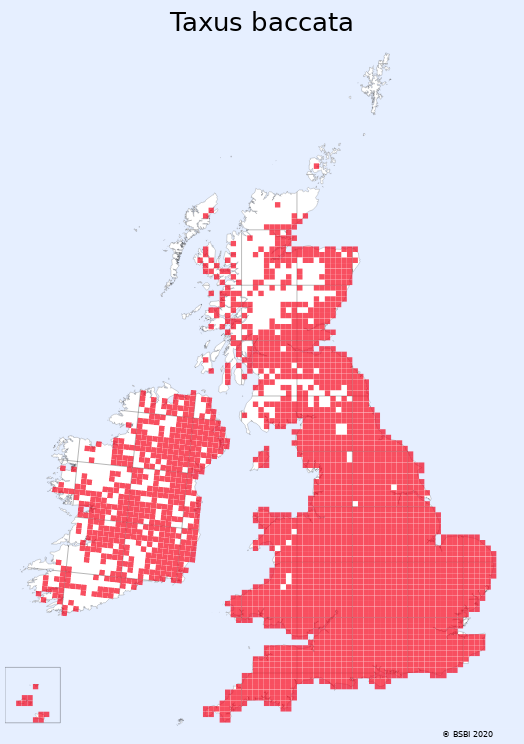

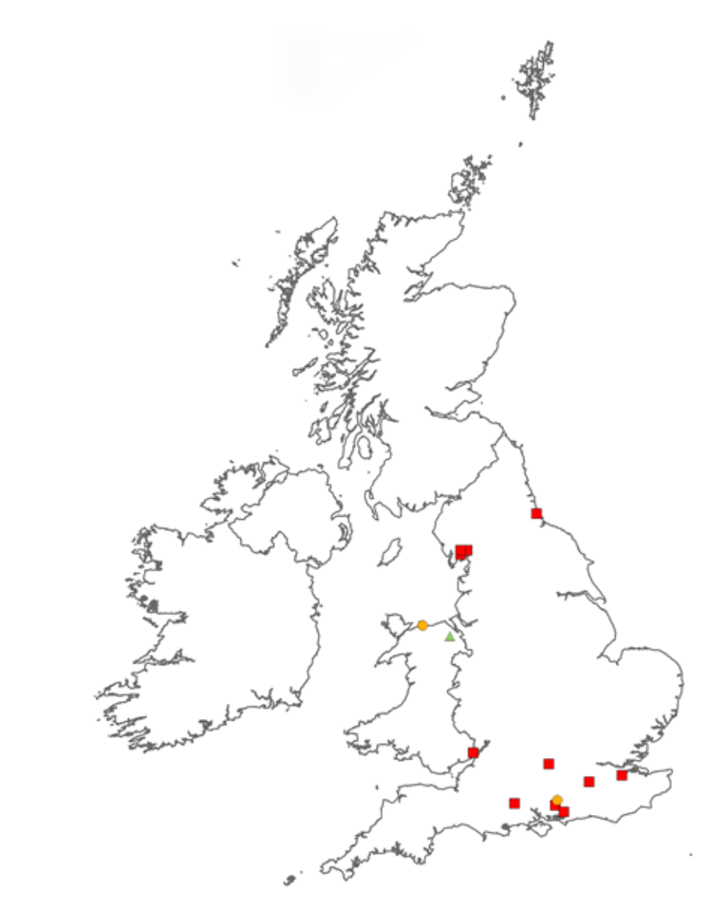

The distribution map (Figure 3), shows the widespread distribution of the species, but the distribution of its natural woodland is very limited (Figure 4). Dickson and Dickson (2000) consider that the introduced versus native status of yew in Scotland is open to question as archaeological remains of the wood, charcoal, pollen as well as artefacts have been found dating as far back as 5500 BCE. The largest stand of yew in Scotland is probably on Inchlonaig Island on Loch Lomond, reputedly planted there in the 14th Century to make bows for Robert the Bruce. Although several of the Inchlonaig trees are large, the most notable Scottish heritage yew trees are to be found at Fortingall (Perthshire), Ormiston (East Lothian) and Whittingehame (East Lothian).

© JNCC

Earliest fossil records date the evolution of the Taxaceae to the Early Jurassic (Philippe et al., 2019). Paleotaxus rediviva is 200 million years old, while the mid-Jurassic species Taxus jurassica, which is 140 million years old, is the first member of the genus which resembles some extant species (Spjut, 2000). Taxus baccata has been around Europe since at least 50,000 BCE, was ousted by ice, then returned to the British Isles after the last Ice Age about 5500 BCE, reached Ireland by 4000 BCE and its northern natural limit, County Durham, about 5000 BCE (O’Connell et al., 1987).

Yew trees are evergreen; the leaves can live for up to eight years. The trees cast a very deep shade, so that almost nothing grows underneath it, but they can also thrive in deep shade. Growth is supported by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi which increase nutrient availability to the roots (Wubet et al., 2003). Yew may produce leafy branches from old branches and trunks, and sometimes from stools. Its root system is shallow, extensive and horizontal, often above ground on calcareous substrates: it can even extend roots over bare rock. If drooping branches touch the ground, or if the tree falls to the ground, they will grow new roots, enabling clones of the tree to survive for a very long time. This is known as layering. An excellent example is the Ormiston Yew, East Lothian (Figure 5). Unlike most Coniferales, yew has adventitious buds on old wood, which can grow when required, as in many angiosperm trees. These make it resistant to repeated pruning, a quality which makes it suitable for hedging.

Taxus baccata is the type species of the genus. The number of species in Taxus depends on who is counting: Wikipedia lists 26, the American Conifer Society lists 13, and Plants of the World online lists 12. These species are known to be closely related and are scattered through the northern temperate region. Indeed, some botanists think that the different species are sufficiently closely related that they constitute geographical variations of T. baccata, and some treat them all as subspecies or varieties (Hess et al., 1967, cited in Voliotis, 1986).

Yew is known for its longevity and its toxicity and is reputed to have spiritual powers. It is variously known as a sacred tree (Chetan and Brueton, 1994) or a symbol of death (Kenicer, 2020), probably because it is often planted in graveyards. Theories abound as to why this should be. Some say that it was worshipped for its longevity, others that it thrived on corpses, suggesting that yew “absorbed the vapours produced by putrefaction” (Turner, 1644 cited in Bevan-Jones, 2004). Since the oldest yew trees in churchyards predate Christianity, their presence there might symbolise some form of pagan resurrection and immortality of the soul. There are also plenty of much more pragmatic suggestions: yew wood is excellent for making longbows, yet it’s toxic, so planting in sheltered churchyards prevented grazing animals being poisoned by it, and provided an effective windbreak.

The oldest yew tree in Scotland is in the churchyard of the Perthshire village of Fortingall near Aberfeldy (Figure 6). Estimates of its age range widely from 1,500 to 9000 years. Its heartwood is unfortunately rotten, so tree rings cannot be counted. The Fortingall yew tree is essentially male, but in recent years some branches changed sex and started to produce ‘berries’ (Coleman, 2015). Likewise, the Ormiston yew, which is essentially female, has been found to sprout male branches (Ancient Yew Group, 2001).

https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5326309 (© Copyright Jim Barton and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons License: CC BY-SA 2.0)

All parts of the yew plant are poisonous except for the berry-like aril. Despite its poisonous properties, yew is very susceptible to browsing and bark stripping by rabbits, hares, deer and domestic animals such as sheep and sometimes even cattle (Thomas and Polwart, 2003) and the levels of toxicity vary seasonally. At least 10 different taxine alkaloids have been identified. All are cardiotoxic and act via calcium and sodium channel antagonism (Garland et al., 1998). It is a bit of a myth that yew is poisonous to browsing mammals but not poisonous to birds. The ‘arils’ are sweet, slightly gelatinous and non-poisonous, but the seed is packed with toxins, and will kill anything that digests it. Since birds have no teeth, they do not break down the seed coat, so they survive. Indeed, frugivorous birds are important dispersers of the seed, either by excretion or regurgitation (Thomas and Polwart, 2003). The human digestive system digests the seed coat, so we are killed. Shakespeare must have known this, for his witches in Macbeth included “slips of yew” in their brew, maybe to rhyme (rather antisemitically) with “liver of blaspheming Jew”.

Even before that, the ancient Celts and Germanic tribes tipped their arrows with yew juice, and Caesar in his Gallic Wars recounts how Cativolcus, the king of the Germanic tribe Eburones, committed suicide by drinking a concoction made from yew, an appropriate end, as ‘eburo’ happens to mean yew. In more recent times there are a few reports of accidental poisonings, mostly in children, but the problem is much greater for grazing animals, particularly horses, whose fields are often edged with yew.

Several Taxus species produce paclitaxel, a valuable anti-cancer, anti-mitotic drug more often known by its brand name Taxol®. Some of the non-pathogenic species of endophytic fungi which live within its inner bark and leaves also produce paclitaxel. When the medicinal value of paclitaxel was first recognised, it was produced from the bark of natural populations of Pacific Yew, Taxus brevifolia, but this was expensive, destructive and non-sustainable. The drug is now manufactured from cultured Taxus cells. The biosynthesis of Taxol® by the tree and its endophytes was investigated by Talbot (2015) and by Soliman et al. (2013, 2015). It appears to be a remarkable, newly-recognized, sort of mutualism: the bark of yew is susceptible to attack by wood-decaying fungi, for which paclitaxel is an effective fungicide, and the yew and its endophytes both benefit from keeping these at bay.

Yew wood is strong, hard-wearing, and, because it is not resinous, fairly incombustible. It is exceptionally elastic, so it has been used for making bows since prehistoric times. British yews tend to be gnarly (see below) and so yew for the English longbows used at the Battle of Agincourt was imported from Spain or northern Italy, where the climate was better for growing suitable yew: indeed, so much yew was cut in the Tyrol for export to England that it became almost extinct there (Spindler, 1994). Ötzi, the Chalcolithic mummy found in 1991 in the Italian Alps, carried an unfinished bow made of yew wood (Spindler 1994). The name Taxus is thought to derive ultimately from Scythian and Persian words for bow or arrow (Mallory and Adams 1978). Other artefacts which can be shaped from the wood include furniture, bowls, boxes, tool handles and combs.

In Norse mythology, the abode of the god of the bow, Ullr, had the name Ydalir (Yew Dales). Despite being evergreen and having red berries, the yew has escaped being a tree we cut at Christmas. It is, however, a frequent symbol in the Christian poetry of T. S. Eliot, especially his Four Quartets.

Taxus baccata is thus an iconic, medicinally and economically important species, whose genetic diversity should be conserved. The International Conifer Conservation Programme (ICCP), is endeavouring to do this at the Royal Botanic Garden, through the Edinburgh yew hedge initiative (Gardner et al., 2019). Since 2014, different genotypes have been planted round the perimeter of the garden. These include clones from all the iconic Scottish trees as well as wild origin material from seed collected throughout their native habitats across the UK, continental Europe, Western Asia and North Africa.

References:

Ancient Yew Group, (2001) https://www.ancient-yew.org/treeInfo.php?link=660 (Retrieved 20/11/2020)

Bevan-Jones, R. (2004). The ancient yew: a history of Taxus baccata. Bollington: Windgather Press. pp. 38–39

Chetan, A. and Brueton, D. (1994) Sacred Yew. Penguin.

Coleman, M. (2015). Oldest yew tree switches sex. Botanic Garden Stories. https://stories.rbge.org.uk/archives/17622 (retrieved 23/11/2020)

Dickson, C. and Dickson, J. (2000). Plants and People in Ancient Scotland. Tempus Publishing Ltd. Gloucestershire.

Dörken, VM., Nimsch, H. and Rudall, PJ. (2019). Origin of the Taxaceae aril: evolutionary implications of seed-cone teratologies in Pseudotaxus chienii. Annals of Botany, 123(1) pp.133–143.

Gardner, M., Christian, T., Hinchcliffe, W and Cubey, R. (2019). Conservation Hedges – Modern-Day Arks. Sibbaldia 17, 71-100.

Garland, T. and Barr, CA. (1998). Toxic plants and other natural toxicants. International Symposium on Poisonous Plants (5th: 1997: Texas). Wallingford, England: CAB International. ISBN 0851992633. OCLC 39013798.

Kenicer, G. (2020). Plant Magic. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

Mallory, JP., and Adams, DQ. (1997). Encyclopaedia of Indo-European culture. London [etc.]: Fitzroy Dearborn. p.78. JP Mallory and DQ Adams (eds.), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, London – Chicago 1997, 829 pages, ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

O’Connell, M., Mitchell, FJG., Readman, PW., Doherty, TJ. and Murray, DA. (1987). Palaeoecological investigations towards the reconstruction of the post-glacial environment at Lough Doo, County Mayo, Ireland. Journal of Quaternary Science 2 pp.149–164.

Philippe, M., Afonin, M., Delzon,S., Jordan. G.J., Terada, K., Tiebaut, M. (2019). A paleobiogeographical scenario for the Taxaceae based on a revised fossil wood record and embolism resistance. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 263 pp 147-158.

Plants of the World Online http://plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (retrieved 27/9/2020)

Soliman, SSM. and Raizada MN. (2013). Interactions between co-habiting fungi elicit synthesis of Taxol from an endophytic fungus in host Taxus plants. Frontiers in Microbiology 4(3). DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00003

Soliman, SSM., Greenwood, JS., Bombarely, A., Mueller, LA., Tsao, R., Mosser, DD. and Raizada, MN. (2015). An endophyte constructs fungicide-containing extracellular barriers for its host plant. Current Biology 25(19) pp.2570-2576.

Spindler, K. (1994). Der Mann im Eis. Goldman Verlag. Munchen.

Spjut, RW. (2000) Introduction to Taxus. http://www.worldbotanical.com/Introduction.htm (Retrieved 22/11/2020)

Talbot, NJ. (2015). Plant Immunity: A Little Help from Fungal Friends. Current Biology 25(22) pp. R1074-R1076.

Thomas PA, and Polwart, A. (2003) Taxus baccata L. Biological Flora of the British Isles No. 229 List Br. Vasc. Pl. (1958) no. 35, 1. Journal of Ecology 91 pp. 489–524. Taxus baccata L. (wiley.com)

Tittensor, RM. (1980) Ecological history of yew Taxus baccata L. in southern England. Biological Conservation 17 pp.243–265.

Voliotis, D. (1986) Historical and environmental significance of the yew (Taxus baccata L.). Israel Journal of Botany 35 pp.47–52.

Wubet, T., Weiss, M., Kottke, I. and Oberwinkler, F. (2003) Morphology and molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in wild and cultivated yew (Taxus baccata), Can. J. Bot. 81: 255–266.

Yews in Spain (no date) http://www.iberianature.com/material/yew_spain.htm (retrieved 23/11/2020)

Roger West and Maria Chamberlain