The Hairy Bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta) is one of the first plants to flower in the spring. It’s a small plant, easy to find in most streets, where it grows along the edges of pavements, but can be confused with the closely-related C. flexuosa. They are both very common throughout the British Isles. Both have the English name ‘bittercress’ but C. hirsuta is the Hairy Bittercress and C. flexuousa is the Wavy Bittercress.

The characteristic rosette of C. hirsuta, just before flowering. Image: Chris Jeffree

Cardamine belongs to the Cabbage and Mustard Family (the Brassicaceae) and there are about 200 Cardamines in the world. Here in Britain we have five main species: as well as the Hairy and the Wavy we have the familiar Cuckoo Flower (C. pratensis), the Large Bitter-cress (C. amara) and the Narrow-leaved (C. impatiens). In a previous blog we showed the tiny newly-arrived alien, Cardamine corymbosa the New Zealand Bittercress. It is still rare, but it has turned up in my Edinburgh garden, in the crazy paving. Are my shoes an agent of dispersal?

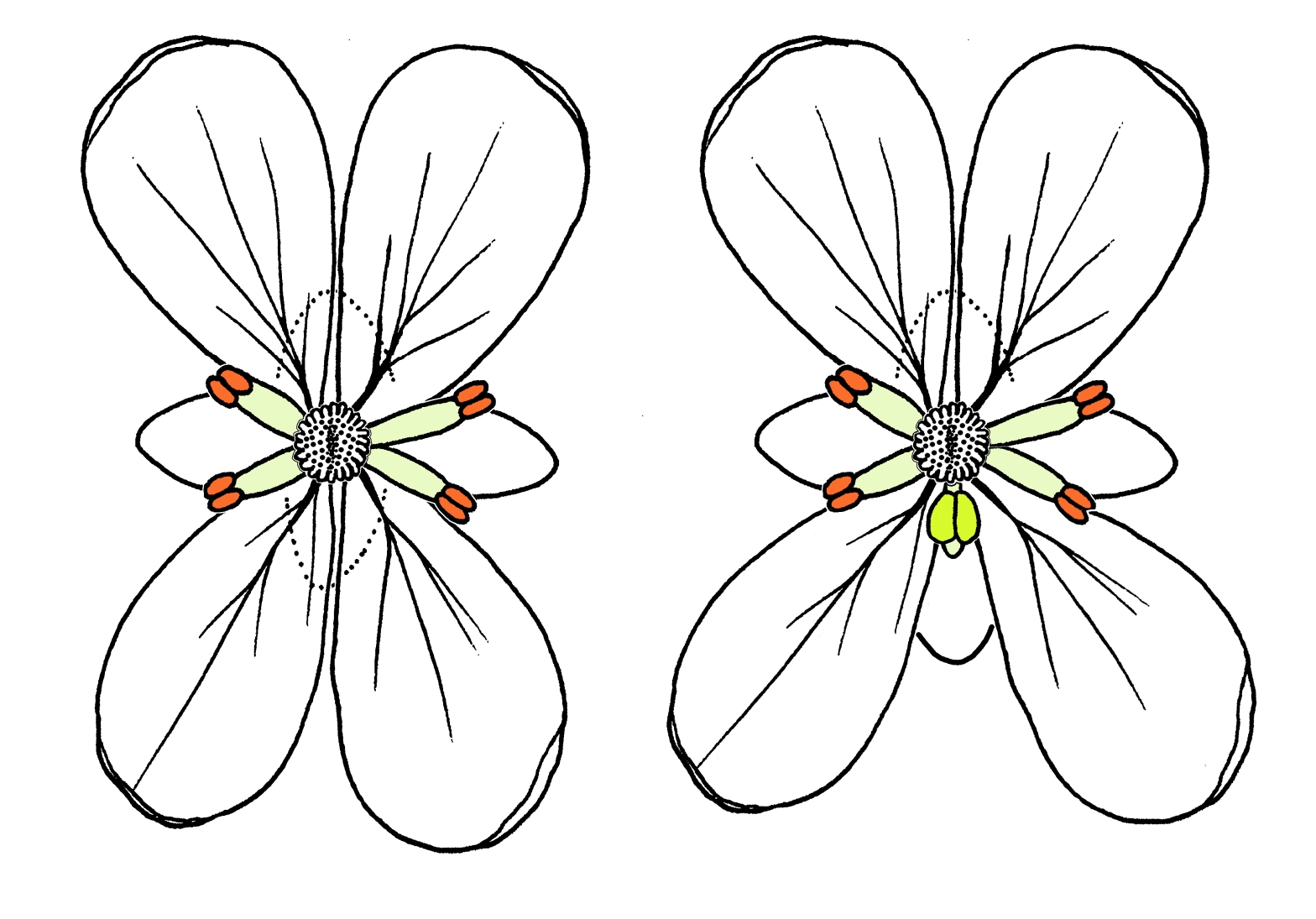

The two commonest bittercresses: left, Cardamine hirsuta; right, C. flexuosa. Note: in C. hirsuta the young pods frequently overtop the flowers; the stem of C. flexuosa is markedly ‘wavy’ i.e. flexuose. The name hirsuta means hairy but C. hirsuta is no more hairy than C. flexuosa. Images: Chris Jeffree.

Whilst the Hairy and the Wavy are very common all over Britain, it is the Hairy (C. hirsuta) that is the most common in our towns, cities and gardens. It is an annual plant, described as a ‘winter annual’. Seeds are shed in the early summer but they do not usually germinate until the autumn. There is apparently an in-built dormancy mechanism, which is not well-understood. The plant overwinters as a small rosette, then bursts into life in March and April as soon as temperatures rise. Some seeds may not germinate in the year of shedding; they remain in the soil, forming the ‘seed bank’. Thus, in a poorly managed garden plot, frequent hand-weeding is required; otherwise more than one generation can form within a year. This helps to explain its success as a cosmopolitan ‘weed’. In contrast, C. flexuosa can be an annual, a biennial or a perennial. Its flowers come a little later, starting in May.

Contrasting flowers of C. hirsuta (left) and C. flexuosa (right). They differ in the number of stamens (four in hirsuta, six in flexuosa). Also the flowers of hirsuta have a tendency towards bilaterally symmetry. It may be significant that the stigma of C. hirsuta sometimes protrudes out of the bud before it has opened, so there is less deposition of its own pollen from the early stamens than in C.flexuosa. Images and interpretation: Chris Jeffree.

Telling the difference can be challenging, and the two species often occupy the same habitat. Tim Rich, in his BSBI book Crucifers of Great Britain and Ireland, helpfully lists the characters in order of importance:

“Number of stamens, number of stem leaves, hairiness of the stem”.

This example of C. hirsuta has an extra stamen (five not four). In some cases, there are two extra stamens. Image: Chris Jeffree.

C. hisuta usually has 4 stamens, not the six found in C. flexuosa, but you need a lens and a steady hand to make the count. You may be thwarted: sometimes the flowers refuse to open: C. hirsuta can be cleistogamous in cold weather. As for the character “number of stem leaves” C. hirsuta has fewer: usually 1-4 whereas C flexuosa has 4-10.

Is C. hirsuta hairy? Only faintly so. I think hairiness of the stem is not a very useful character – both species can be somewhat hairy and flexuosa seems to be more hairy than hirsuta. Surely better characters for identification are plant height and waviness of the stem? C. hirsuta has stems 5-30 cm tall whereas in C. flexuosa they are 7-50 cm tall and nearly always wavy (‘flexuose’). Different books give different dimensions; the plants I in Scotland are usually near the lower limit.

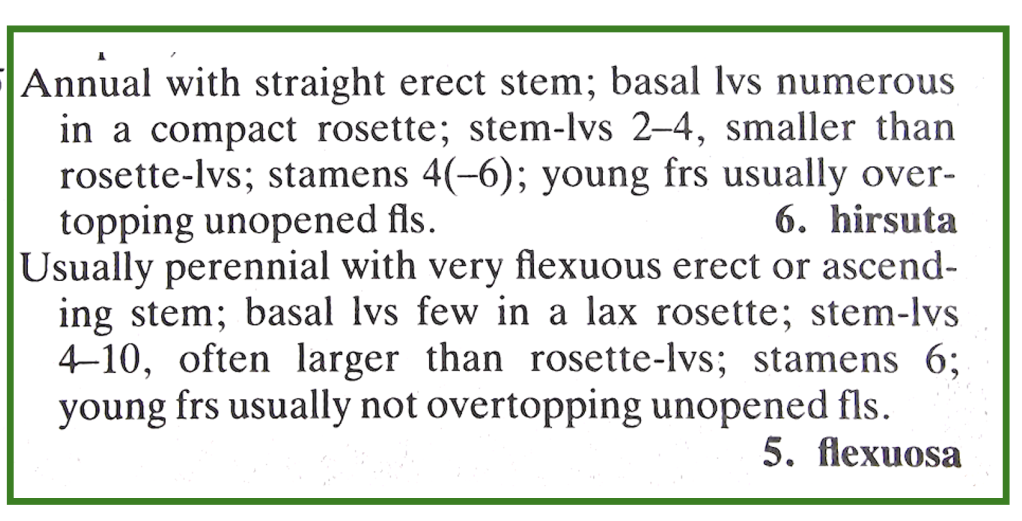

Readers may be interested in the key differences between the two species as described in Flora of the British Isles (Clapham et al 1987):

No mention is made of stem hairiness in Clapham’s key, but the character ‘young fruits usually overtopping unopened flowers’ does feature.

Early botanists struggled to tell the two species apart, but the parson-naturalist John Ray succeeded in the late part of the 17th Century (Pearman 2017). These plants are definitely different species, as shown by their chromosome count which is 2n=16 (hirsuta) and 2n=32 (flexuosa). In situations where they grow together they may hybridise. The hybrids have sterile pollen but they look like C flexuosa and so they may escape the attention of recorders.

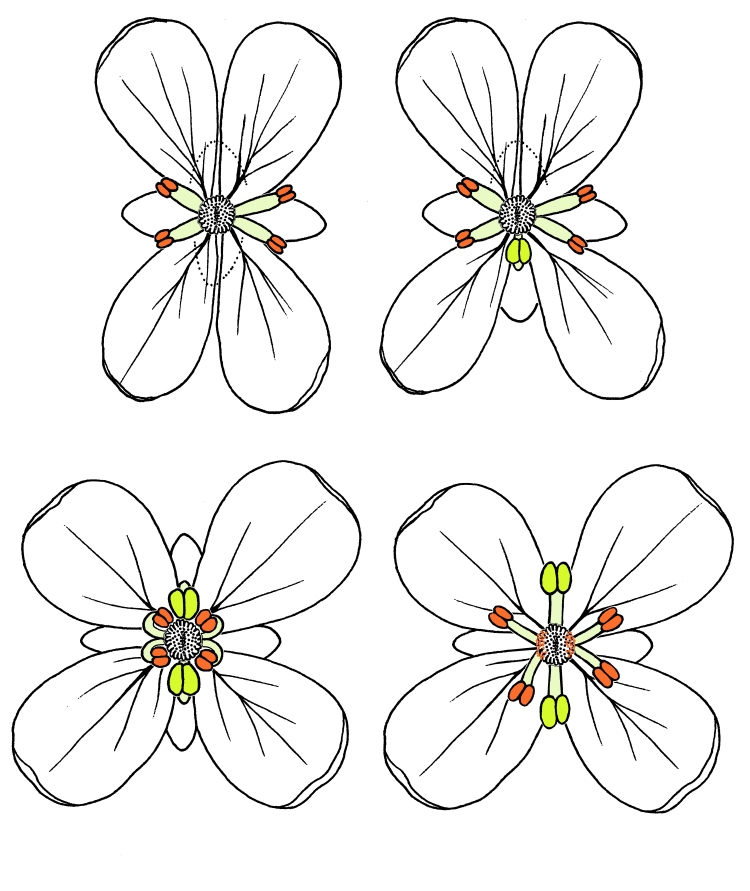

Drawings of flowers by Chris Jeffree. Top: hirsuta, lower: flexuosa. Note the relative petal and stamen positions in the two species. It seems there are two sorts of stamens (Matsuhashi et al. 2011), ‘medial’ (anthers shown red here) and ‘lateral’ (shown as green). According to Matsuhashi et al. (2011) development of laterals in hirsuta is temperature dependent.

Both have an explosive seed dispersal mechanism well-described and illustrated in Edward Salisbury’s book Weeds and Aliens. The seed pods open abruptly and each one flings about 20 seeds to a distance of up to 30 cm., hence the alternative name for C. hirsuta ‘Popping Cress’. You can watch the popping on this short movie-clip. Recent work explores the genetic control of how lignin strands are formed in the seed pods and how the necessary tensions build up immediately before the explosion (Hofhuis and Hay 2016, Pérez-Antón et al 2022). The latter authors claim a dispersal distance of up to a metre. As I was pondering the limits of seed dispersal by this ‘flinging’ process, I came upon another paper which claimed a distance of 5 metres (Vaughn et al 2011). Perhaps this one was wind-assisted.

C. hirsuta growing as a garden weed. Image: Chris Jeffree.

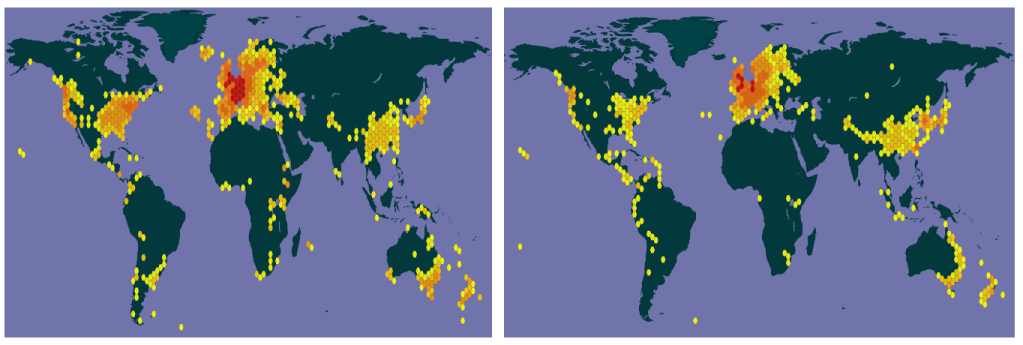

Grime et al (1988) describe the ecological characteristics of these species. Both are generally found in open habitats on base-rich soils with a pH of 6-7, but C flexuosa appears more often in woodlands (hence its alternative name Wood Bittercress), and seems to tolerate rather wet conditions. The BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020 states that C. flexuosa is increasing, saying this:

“There has been a notable increase in the known distribution of this widespread species since the 1960s. Increases in parts of eastern England, Scotland and Ireland are likely to be due to more systematic recording and also its frequency as a weed of container-grown garden centre plants, with C. flexuosa subsequently found in urban environments following seed dispersal or the dumping of garden waste”.

Global distribution of Cardamine hirsuta (left) and C. flexuosa (right). From GBIF.

Of the two species, C. hirsuta is more likely to be found in dryer habitats including rocky outcrops and walls, and it is more often a garden weed.

One pointer to the critical ecological difference between hirsuta and flexuosa comes from Japan. There, flexuosa is a native plant that grows partially submerged in rice paddy fields. Seeds of the invasive European ‘weed’ hirsuta cannot stand getting wet and so it hasn’t invaded the fields (Yatsu et al 2003). You may enjoy this open access article from Japan.

Most readers of these pages will know the iconic Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale Cress), a closely-related and early-flowering member of the same family. It doesn’t fling its seeds, it merely lets them fall. A. thaliana was chosen several decades ago as the model organism for studies into gene regulation of plant traits because of its short (6-week) life cycle and conveniently small size. We reviewed it in 2020 (see here). Now, several researchers are turning to Cardamine hirsuta as an alternative (Hay and Tsiantis 2006, Gan et al 2016). I wonder if they know about the inconvenient summer dormancy of the seeds?

Foragers like to collect C. hirsuta. One website describes it thus:

“This plant tastes like cress crossed with rocket and is one of our favourite edibles. Great for salads, salsa, pestos and anywhere you would use cress raw, cooking, unfortunately, seems to remove the flavour”.

I tried it once in a sandwich and I liked it. Beware of collecting it from street populations as four-legged friends may have added to its flavour and roadside dust will collect on its leaves and stems.

Notes on other species of Cardamine

The native Cardamine pratensis (known as Cuckooflower or Lady’s Smock) is flowering now. We wrote about it last year – see our blog here. This is a fairly common plant of seasonally-wet grasslands on fertile soils. Flower colour can vary from white to violet.

Cardamine pratensis (Cuckooflower). Image: Chris Jeffree.

Cardamine impatiens, the Narrow-leaved bitter-cress, is an alien species, first recorded in Hampshire in 1916. It has been recorded only a few times in Scotland and Ireland, and its distribution in England and Wales is patchy. It grows on lime-rich soils and it can be found in the grikes of limestone pavments and in ash woodlands. It is quite different from C. hirsuta and C. flexuosa (it has narrow leaflets that are toothed).

Cardamine impatiens. Images: Richard Milne.

References

Clapham AR et al (1987) Flora of the British Isles, 3rd edition Cambridge University Press.

Gan X et al (2016)The Cardamine hirsuta genome offers insight into the evolution of morphological diversity. Nature https://www.nature.com/articles/nplants2016167

Grime JP et al (1988) Comparative Plant Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-1094-7

Hay A and Tsiantis M (2006) The genetic basis for differences in leaf form between Arabidopsis thaliana and Cardamine hirsuta. Nature Genetics https://www.nature.com/articles/ng1835

Hofhuis H et al. (2016) Morphomechanical Innovation Drives Explosive Seed Dispersal. Cell, 166, 222-33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.002

Matsuhashi S et al. (2012) Temperature-dependent fluctuation of stamen number in Cardamine hirsuta.International Journal of Plant Science 173, 391-398.

Pearman D (2017) The Discovery of the Native Flora of Britain & Ireland. BSBI.

Pérez-Antón M et al (2022) Explosive seed dispersal depends on SPL7 to ensure sufficientcopper for localized lignin deposition via laccases. PNAS Plant Biology 119. https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.2202287119

Salisbury E (2009) Weeds and Aliens. Collins.

Vaughn KC (2011)The mechanism for explosive seed dispersal in Cardamine hirssuta. American Journal of Botany. https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3732/ajb.1000374

Yatsu Y et al (2003) Ecological distribution and phenology of an invasive species, Cardamine hirsuta L., and its native counterpart, Cardamine flexuosa With., in central Japan. Plant Species Biology https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-1984.2003.00086.x

©John Grace