Caltha palustris is a spring flower that I love to see, coming just after the snowdrops have finished. As its name suggests, Marsh Marigold grows on marshy ground – we usually notice it flowering by the sides of streams, very close to the water level. Its yellow saucer-shaped flowers are a glory.

Flowers are 1-5 cm across, pollinated by insects, and self-incompatible (i.e. cross pollinated). Flowers usually have 5 tepals but often more. Image: Chris Jeffree.

It belongs to the buttercup family, Ranunculaceae. It is native over much of Europe, Asia and North America. Gerard included it in his Herball of 1597 but (unusually for him) he doesn’t suggest any medicinal use. He says:

Marsh Marigold hath great broad leaves somewhat round, smooth, of a gallant green colour, slightly indented or purled about the edges: among which rise up thick fat stalks, likewise green; whereupon do grow goodly yellow flowers, glittering like gold, and like to those of Crowfoot, but greater.

Linnaeus described and named it in 1753, and the name has stuck, although Romanian botanist Dimitrie Brândză (1846-1895) called it Trollius palustris, presumably because he thought it was a close relative of Trollius europaeus the Globeflower.

However, Globeflower has sepals that look like petals, and an inner whorl of petals that are inconspicuous but have nectaries. Marsh Marigold has only petal-like structures that are called ‘tepals’ as there is only one whorl. Its lack of the normal two-whorled flowers has led some botanists to say the flower is one of the most primitive members of the Ranunculaceae, and Clapham et al. (1987) go so far as to say “the flower is perhaps the most primitive in the British Flora”.

Marsh Marigolds are popular with gardeners, and there are many offers on the internet. The selling point is “a great plant for colour in early spring, producing a welcome ball of yellow flowers to brighten your pond after the winter”. Many forms are available, including Plena (the double marsh marigold) and one that is white. I much prefer the wild sort !

Marsh Marigolds being grown for sale to gardeners at Binny Plants. This image shows how the leaves are quite glossy with long petioles. Image: Chris Jeffree.

I have read that some taxonomists in the past have wanted to put Caltha with Helleborus, in a separate Family, the Helleboraceae. The idea did not catch on. Recent work using molecular phylogeny has been useful in resolving the status of Caltha in the Ranunculaceae: it occupies a relatively isolated position, far from Helleborus, and the genus emerged rather recently (about 50 million years ago1) despite looking ‘primitive’ (Cheng and Zie 2013).

Detail of the flower. Note: it doesn’t have petals and sepals as buttercups do, but only one whorl of ‘tepals’. Sometimes they are slightly green underneath. The leaves are without hairs. Image: Chris Jeffree.

Gerard recognised two species of Caltha in 1597: the Great Marsh Marigold and the Small Marsh Marigold. Many years later the Dutch taxonomist Smit (1973) described no less than 55 types of Caltha palustris! But it seems that many of the characters are induced by environmental variations because when plants are grown in a common (wet) environment, they tend to look much the same as each other. In the Flora of the British Isles (3rd edition) Clapham et al (1987) devote much text to describe the variation in Marsh Marigold, and noted the extremely diverse chromosome counts that have been obtained. Stace’s New Flora of the British Isles (4th edition, 2019) is much more concise: Stace mentions a variety called radicans: small-flowered plants with procumbent stems rooting at nodes, found in North Wales, North England, Scotland and Ireland, and another variety with large flowers which is called var. barthei. Stace points out the possibility of garden escapes, including double-flowered types and even white flowered forms. However, both of these highly-regarded reference books present Marsh Marigold as a single species, albeit a variable one.

Detail of fruits. They are ‘follicles’ (a dry fruit that is derived from a single carpel and opens on one side only to release its seeds). The follicles and seeds within seem unripe, and we hope to be able to examine more specimens this year to better understand the structure and to see whether the seeds can float. Image: Chris Jeffree.

Ecological characteristics of Marsh Marigold are described in the work of Grime et al (1987), just one of the many species in their huge survey of the Sheffield region of England. They found Marsh Marigold only in wetlands, ditches and river banks. It can be seen around ponds too. It grows in similar sites as Mentha aquatica and Filipendula ulmaria but unlike these species it usually occurs as solitary individuals, never as crowded stands. It is a perennial: each plant produces a creeping rhizome with ascending shoots, as well as abundant seeds, and may live for 50 years. It is present all over the British Isles (see the map below) but, at a finer scale than the map cannot show, it is declining. According to the BSBI’s Atlas 2000:

The main threats to this species include drainage of wetlands for agriculture, the filling-in of ponds with shallow margins, grassland improvement and a general ‘tidying up’ of wetland habitats”.

Growing within a reed bed. Image: Chris Jeffree.

Spring is here at last, so this week I went looking for Marsh Marigolds. I thought the mild winter might have induced it to flower, but the only flowers were on some throw-outs following the clearing of a garden pond. I found plenty of early blooms on other species: lots of Primroses and a few Lesser Celandines, Spring Beauty and (of course) Dandelions. A vigorous Caltha palustris in a ditch at one of my favourite sites in Dumfries and Galloway has produced a flush of new leaves but no signs of flowers yet. So I looked at the very helpful met office website which summarises monthly variations in temperature and rainfall. They say:

It was the warmest February on record for England and Wales. However, it was not so in Scotland because a cold spell pushed into the north of the UK from the 6th onwards, with temperatures reaching 4.0 to 6.0°C below average in some areas of Scotland and northern England on the 7th and 8th. The south of England, however, experienced consistently mild temperatures throughout this cold spell, leading to a large temperature gradient across the UK.

Those of us living in the cold north of Britain must wait a few weeks more to enjoy the best spring flowers.

Caltha palustris in a ditch, waiting for warmer weather but looking very healthy, 5th March 2024, Leswalt, Dumfries and Galloway. Image: John Grace.

Does it have any useful medicinal properties? The web site Letsgoplanting says:

Caltha palustris has a long history of use in traditional medicine and folklore. It is native to the UK and Europe, and has been used for centuries as a medicinal plant. The ancient Greeks, Romans, and Anglo-Saxons all used it to treat a variety of ailments, including skin conditions and respiratory issues. In the Middle Ages, the plant was believed to have magical properties and was used in rituals and spells. The flowers were also used to make a yellow dye for fabrics.

Many of the chemical compounds that have been extracted from Caltha are biologically active. A recent description can be found in the report of Liakh et al (2020).

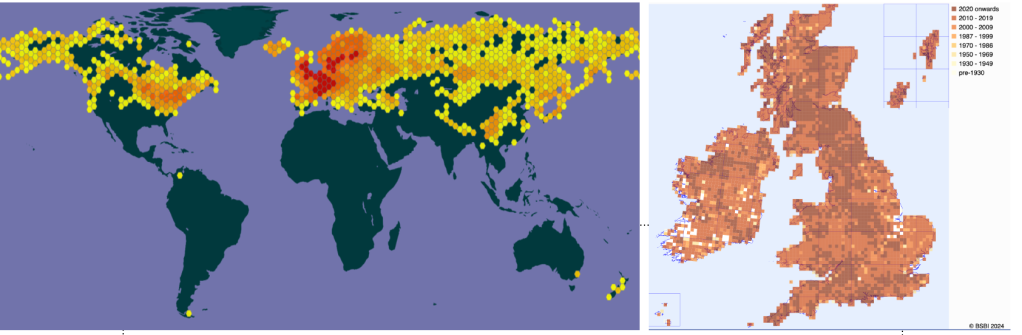

Left: Global distribution according to GBIF. Caltha palustris is native in Europe, Asia and North America. Right: Britain and Ireland, from BSBI Maps (the species has been recorded in almost every square).

Foragers sometimes praise the virtues of Marsh Marigold, as here. However, it is a toxic plant, and people have died after eating it (Lee and Sung 2021). Tibetans sometimes eat it, but only after drying and fermenting (Kang et al 2014). Gardeners World say “Caltha has no toxic effects reported” but they are wrong! All members of the buttercup family contain a compound called Protoanemonin. They should know better.

Footnote

1In evolution, the Ranunculaceae are among the earliest Families, appearing in the Early Cretaceous (122-126 million years ago). Caltha is a small genus compared to Ranunculus itself, and thought to date from 50 million years ago (it is ‘young’ despite looking ‘primitive’. It now has 12 species, strangely disjunct between north and south hemispheres.

References

Cheng J and Xie L (2013) Molecular phylogeny and historical biogeography of Caltha (Ranunculaceae) based on analyses of multiple nuclear and plastid sequences. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 52, 51-67.

Clapham AR, Tutin TG and Moore DM (1987) Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge.

Grime JP, Hodgson JG and Hunt R (1988) Comparative Plant Ecology. Unwin Hyman.

Kang Y et al. (2014) Wild food plants used by the Tibetans of Gongba Valley (Zhouqu county, Gansu, China). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-20

Lindborg R et al. (2021) How does a wetland plant respond to increasing temperature along a latitudinal gradient? Ecology and Evolution, 11,16228-16238. doi: 10.1002/ece3.8303.

Lundqvist A (1992) The self-incompatibility system in Caltha palustris (Ranunculaceae). Hereditas, 117, 145–151.

Marčenko E et al. (1989) Carbon uptake in aquatic plants deduced from their natural 13C and 14C content. Radiocarbon, 31, 785-794.

Schuettpelz E and Hoot SB (2004) Phylogeny and biogeography of Caltha (Ranunculaceae) based on chloroplast and nuclear DNA sequences. American Journal of Botany, 91, 247–253.

Smit PG (1973) A revision of Caltha (Ranunculaceae). Blumea, 21, 119–15

Stace C (2019) New Flora of the British Isles. C&M Floristics.

Stroh PA et al. (2020) Caltha palustris L. in BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020.https://plantatlas2020.org/atlas/2cd4p9h.f36

©John Grace