This tree belongs to an ancient family of trees that first appeared around 190 million years ago, the Araucariaceae, which expanded and diversified in the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, forming extensive vegetation over the supercontinent of Gondwana. Araucaria araucana has a strange ‘prehistoric appearance’ that attracted gardeners in the Victorian era, and inspired widespread planting on the estates of the landed gentry and in the gardens of keen amateurs throughout the country. Many of these early plantings survived, and are sometimes added to, even today. This is such a distinctive and tall tree, that in towns and cities across the country it is rather easy to find a Monkey Puzzle tree.

Three specimen trees planted in 1844 at Castle Kennedy, Dumfries and Galloway (Image: John Grace).

Araucaria araucana comes from Chile and Argentina. How did it get to our shores? The story is told by WJ Bean in his book Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles. The plant collector Archibold Menzies, from Weem in Perthshire, was employed as a surgeon-naturalist to accompany Captain George Vancouver for a world-wide voyage on board the HMS Discovery (1791–1795). Towards the end of the journey, the senior officers were in Valparaíso dining with the Viceroy of Chile, and nuts were part of the dessert. Menzies surreptitiously slipped a few of them in his pocket and later was able to germinate them aboard ship. He returned to England with five seedlings, one of which was still growing as a mature tree at Kew Gardens in 1891. More introductions of this curious tree followed.

The base of this tree is a pedestal of roots, resembling a reptilian foot. Image: John Grace.

Araucaria araucana is a large and long-lived gymnosperm tree. In Chile, the tallest are 45 metres and the oldest exceed 1000 years old (judged from counting their annual growth rings). The trunk is cylindrical and the branches are produced in regular tiers of five to seven. The leaves are triangular, extremely tough, sharply-pointed and long-lived. The mean life span of the leaves (24 years) is among the highest ever reported for any plant species (Lusk 2001).

It is a prickly tree, enough to discourage even the dinosaurs. Note that this young tree has leaves still attached to the main stem, because leaves remain for more than 20 years. Image: John Grace.

The trunk often stands on a pedestal of roots, the whole arrangement resembling the foot of a giant reptile. The species lived in the age of giant reptiles, and it is likely that some of them ate the nuts and the young shoots. Long necks would be essential, and the Sauropod-dinosaurs not only had long necks but they could rear up on their hind legs to browse the tops of trees (Hummel et al 2008). However, sceptics have questioned whether their reptilian hearts were powerful enough to pump the blood to the brain (20 metres above).

The bark is very thick (10-15 cm), a feature that may enable the plant to survive fire.

There are usually separate male and female trees (i.e. they are dioecious, but exceptions occur). The male cone is ovoid and 8-12 cm long, whilst the globose female cone is up to 20 cm in diameter, with around 200 seeds per cone. The species is wind-pollinated, and the female cones take two years to produce mature seeds. There are ‘mast years’ (as in many trees species) when abundant seeds are produced.

Growing shoot-tip, showing extreme points to the spirally-arranged leaves even at an early stage. Image: Chris Jeffree.

The tree forms a component of mountain forests in the Chilean Andes and adjacent southwestern Argentina, extending to the timber-line at around 1800 metres above sea level, and occasionally with southern beech (Nothofagus pumilio or N. dombeyi). In Chile, since 1976 it has been deemed a Chilean Natural Monument. The native Mapuche inhabitants collected the seeds for food (the seeds fall from the ripe cones in the Autumn) and historically the long straight trunks have been harvested for timber, for railway sleepers, and to make the masts of sailing ships. Logging was finally banned in 1990. It is now on the IUCN Red List as ‘Endangered’ because of centuries of land clearance and wild-fires. It is possible that the trees established well beyond the native range, especially in Europe, have greater genetic diversity than the remaining native populations.

Climatic warming may pose a significant threat to the montane forests of South America, as discussed in a recent article by Nagy et al (2023).

Avenue of Monkey Puzzles at Castle Kennedy. Note in the foreground, trees of other species that were brought down in recent storms. February 2024. Image: John Grace.

The best place to see the tree in Scotland is Castle Kennedy, near Stranraer in Dumfries and Galloway. An avenue of these trees was planted in 1844, and despite damage in a great storm early in their lives, most of them remain. The ‘Scottish Champion’ specimen is there, the green plaque declaring the tree to be 27 metres tall. There have been some severe storms in recent years, but these trees seem to be well-anchored whilst many other species have succumbed.

I went to Castle Kennedy last weekend, hoping to find a fallen tree as I wanted to examine the cones. However, all trees of this species were standing despite recent storms. We searched for tree-top cones with binoculars. The female cone breaks up while still on the tree (that is, according to Mitchell 1974, but there are some articles which say otherwise), and so it can be difficult to record the appearance of the cones over the two-year period of maturation. I was however able to photograph a few immature cones borne on the top-most branches. Then, searching in the leaf litter I found the bedraggled remains of a male cone. WJ Bean evidently visited Castle Kennedy many years ago and writes that he saw seedlings springing up from seeds that had fallen. I saw only two or three. Searching in the leaf litter I found the remains of one male cone. I suspect the cones are predated upon by squirrels.

Left: Developing female cones in the tree-top. Most of the Castle Kennedy trees had no cones visible in February 2024 and only this tree had many visible cones. Image: John Grace. Right: male cones. Image: Kurt Stüber [1], CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/,

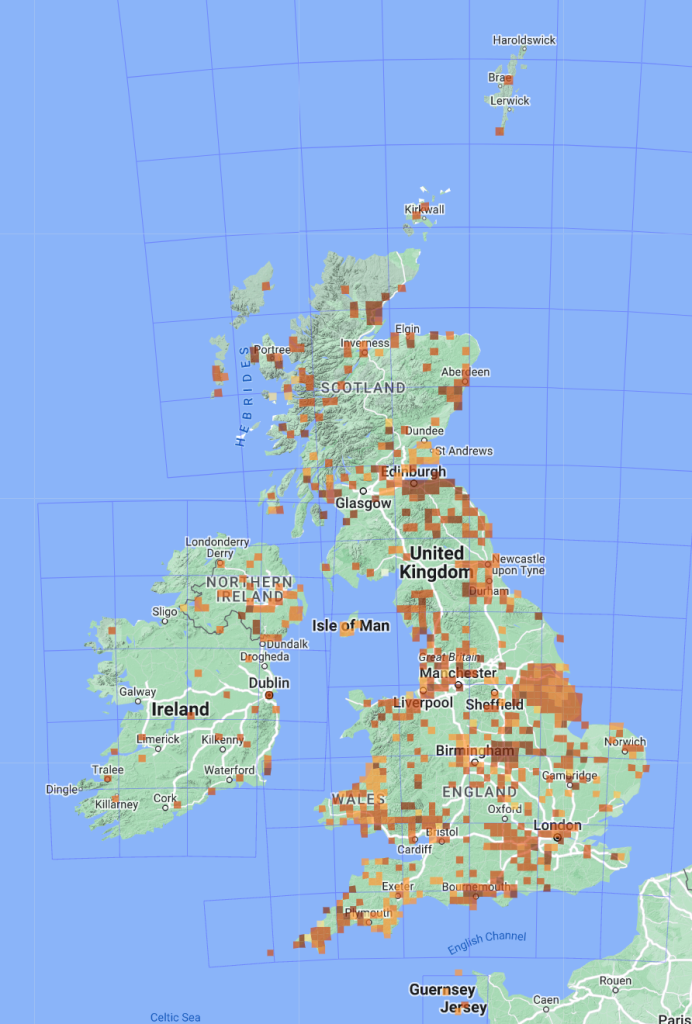

Monkey Puzzle is one of the hardiest trees ever introduced to Britain, tolerating minus 20 degrees C. It is also known to be the most hardy of all Araucaria species (there are 35 species world-wide). Its distribution in Britain demonstrates its tolerance of a wide range of climates, from Penzance in the south to Lerwick (Shetland) in the north. It is however said to be intolerant of pollution, and the British distribution seems to show that: it is absent or rare in the most historically-industrialised parts of the country.

British and Irish distribution of Araucaria araucana, from the BSBI.

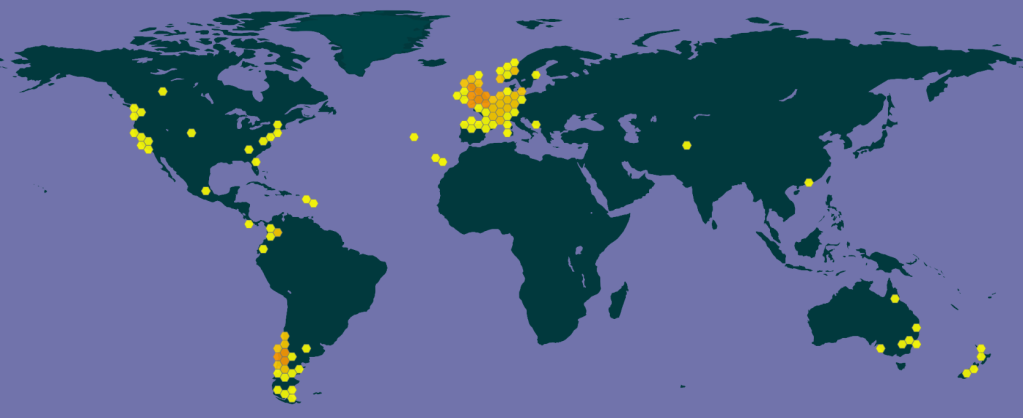

The world-wide distribution is somewhat misleading, dominated by the cluster in Europe, where Monkey Puzzle has been planted in gardens and parkland. The tree is native only in Chile and Argentina. For the Araucariaceae as a whole, there are 35 known species, and they belong primarily to the southern hemisphere. The tiny French territory of New Caledonia, with a land mass somewhat smaller than Wales, has 20 species of Araucaria and 13 are endemic. It is considered that such a proliferation of species can only be the result of rather recent evolution on a geographically-isolated island (reminding me of Darwin’s Finches on Galapagos). An alternative explanation is that these are relict species of Gondwana, the supercontinent that later became South America, Africa, India, Australia and New Zealand.

Global distribution of Araucaria araucana, from GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). The tree is native only in Chile and Argentina.

References

Bean WJ (1970) Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles. Eighth Edition. Murray, London.

Hummel J et al. (2008) In vitro digestibility of fern and gymnosperm foliage: implications for sauropod feeding ecology and diet selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275, 101501021. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1728. PMC 2600911. PMID 18252667.

Lusk C H (2001) Leaf life spans of some conifers of the temperate forests of South America. Longevidad foliar de algunas confferas de los bosques templados de Sudamprica. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 74, 711-718.

Mitchell A F (1974) A field guide to the trees of britain and northern europe. Collins

Nagy L et al. (2023) South American mountain ecosystems and global change – a case study for integrating theory and field observations for land surface modelling and ecosystem management, Plant Ecology & Diversity, 16, 1-27. DOI: 10.1080/17550874.2023.2196966

©John Grace