Lapsana communis by Carl Axel Magnus Lindman, public domain image, via Wikimedia Commons. Lindman (1856 – 1928) was a Swedish botanist and botanical artist, known for his work “Bilder ur Nordens Flora” (1901-1905).

Nipplewort, Lapsana communis, is an annual plant (but with a rare perennial subspecies) belonging to the Asteraceae (Daisy Family). We have recorded it over 600 times in the Urban Flora of Scotland project. It turns up in many habitats, including walls, roadsides and tracks, wood margins, hedges and gardens. These habitats are often fertile and moist, with a pH above 6.0, and then the plant can grow to about 1 metre but much less in poorer soils. The species is widespread in Britain and Europe, where many gardeners think of it as a ‘weed’.

Nipplewort flowering in a hedgerow at Livingston, July 2023. Photo: John Grace

The pale yellow ‘flower’ is made up of 8-15 florets each with a tongue-like extension (‘ligule’). The whole structure opens wide in bright weather but may close in the afternoon or remain completely closed if the weather is unfavourable. The upright stems sway in any slight breeze and attract pollinating insects including syrphid flies, house-flies and bees. Also the dagger fly, Empis pennipes L. and the cabbage butterfly Pieris rapae L. show an interest. The stamens are sensitive to touch, moving towards the touch-point and releasing pollen at the top of the anther, depositing it on any insect that has been attracted to the nectar (Proctor and Yeo 1975). Many are thus cross pollinated, but self-pollination occurs too.

The ‘flower’ made up of 8-15 florets, each fully hermaphrodite and capable of former a seed after cross-pollination or self-pollination. Photos: John Grace.

The seeds are rather numerous (500-800 per plant) banana-shaped (see the illustration by Carl Lindman above) and about 4.5 mm long, but they lack the pappus of hairs that enable wind dispersal in many of the Asteraceae (dandelion, for example). In this case, seeds are simply shaken out by the wind. Some of them may germinate in the autumn to form overwintering rosettes, or they may wait for the spring. Growth is rapid and flowering occurs between June and September. The seeds remain viable for six years and can occur as contaminants in batches of agricultural seeds, helping to perpetuate the species.

Developing seeds in the capsule which is formed from the bracts around the inflorescence. Some people have remarked that the structure looks like a pepper-pot. Photos by John Grace.

Only the laziest of gardeners should complain about this plant as a weed, as it can easily be pulled from the ground. It has a rather feeble tap root, and tugging the stem generally uproots the whole plant whenever the soil is reasonably friable. There is no need to resort to herbicides. I suspect the tap root is better-developed in those individuals that have germinated in the autumn, and that it is really an organ of storage rather than one of anchorage, enabling rapid growth in spring. The image below is the root of one individual pulled from the ground with the soil shaken off.

The root system of Nipplewort, Photo: John Grace.

As with many Asteraceae species, Nipplewort has secretory cells that make a white milky latex (‘laticifers’) which are evident when the leaves are torn or the stem cut. It is however much less productive in this respect than the sow thistles and dandelions. The composition of milky latex is quite complex, with enzymes that break down proteins and in some species there are small quantities of rubber. It is assumed by many that the latex is part of the plant’s defences against herbivores. For a discussion of latex, please take a look at Hagel et al (2008).

We have said the species is very common in Britain but is it a native species? This is not completely certain, and Stace’s New Flora of the British Isles simply says “probably native”. However, it seems to have been here when the Romans were in Britain around 2000 years ago (plant remains have been found at an archaeological site known as Coulter’s Garage, Alcester, Warickshire) and quite common in Winchester in the 10th – 15th Century (Green 1975). Moreover, it is native according to Plants of the World Online. It does occur in Gerard’s 1597 Herbal but his illustration is incorrect. Pearman (2017) suggests its first record was from 1578 when Henry Lyte (1529-1607), who called it Lampsana, wrote it “groweth most commonly in all places, by high way sides, and especially in the borders of gardens amongst wortes and potherbes”. Henry Lyte was the author of the Niewe Herball, but this book was a translation from the French book by Charles L’Ecluse, which itself was a translation of the 1554 herbal called Cruydeboeck by the Flemish author Rembert Dodeons. Lyte’s illustrations were from the original Flemish woodcuts. Plagiarism appears to have been an unknown concept in those days, but Lyte used a different typeface for his own comments. I conclude that Lyte’s work refers to the Flemish occurrence of Nipplewort, not the British. However, taking the archaeological evidence into account it seems that the species has been here since Roman times at least.

Henry Lyte and the relevant page of his Herbal with an illustration of Lapsana which he called Lampsana.

The rare subspecies intermedia has a strange highly-scattered distribution, and perhaps it has been overlooked by recorders. I haven’t seen it but I will look out for it (now I know of its existence!). According to Stace’s New Flora of the British Isles the most obvious characters to look for are that the flowers are larger and it is “usually perennial”. You can find an image from North Wales here. It came from SE Europe long ago, perhaps as a garden ornamental.

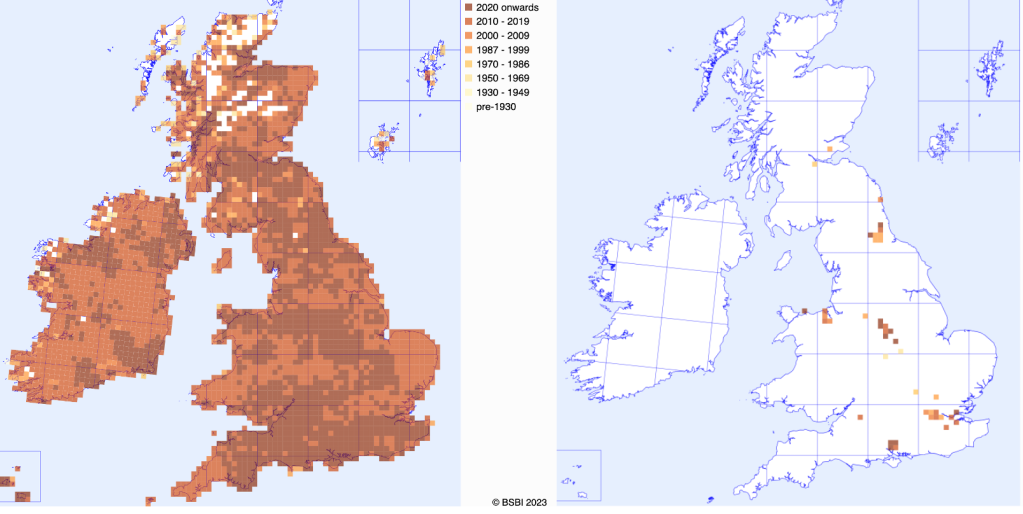

Distribution, from BSBI/Maps. Lapsana communis (left) and Lapsana communis Ssp. intermedia (right).

World-wide, the species was travelled far, to North and South America, the Far East and Australasia (see the map below – unfortunately the map-makers at Kew have excluded important parts of the Southern Hemisphere including New Zealand). The most comprehensive account of the species I have found is from Canada (Francis et al 2011). These authors give dates of first records in Canada as 1833 and for the USA, 1884. They suggest it was transported with garden materials or as a medicinal herb.

World distribution according to Plants of the World Online. Green is where the species is considered to be native, and purple is the introduced range.

The English name Nipplewort was coined in the 17th Century. According to the ‘doctrine of signatures’ the flower buds’ resemblance to nipples implies this species is good for treating ailments of the nipples. German apothecaries had used it for cracked nipples and ulcerated breasts.

Plants for a Future says the leaves are edible, and can be used in salads or cooked like spinach. But the ones I tried were too bitter. As with many latex-producing species, Nipplewort has occasionally been investigated as a source of oil. The seeds may have 6 per cent of oil.

References

Francis A, Darbyshire SJ, Clements DR and DiTommaso A (2011). The Biology of Canadian Weeds. 146.Lapsana communis L. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 91, 553-569.

Green FJ (1979) Plant Remains: methods and results of archaeobotanical analysis from excavations in southern England with especial reference to Winchester and urban settlements of the 10th – 15th centuries. Masters thesis, Southampton University.

Hagel JM (2008) Got milk? The secret life of laticifers. Trends in Plant Science, 13, 631-639

Pearman D (2017) The discovery of the native flora of Britain & Ireland. BSBI, Bristol.

Proctor M and Yeo P (1975) The Pollination of Flowers. Collins.

Stace CA (2019) New Flora of the British Isles. C&A Floristics.

©John Grace