Rushes are members of the flowering plant family Juncaceae, which contains a handful of genera, most of which are native to the southern hemisphere. In the northern hemisphere, two genera are important – Juncus, the rushes and Luzula, the woodrushes.

Stace lists 31 species of Juncus in the British Isles, of which several species are wool aliens, their seeds having been transported in wool bales to the woollen mills of the midlands. Notable among these is the great soft rush J. pallidus, native to Australia and New Zealand, which is like a very large Juncus effusus.

The four species described here are all in Juncus Section Juncotypus and include some of the largest and commonest native rushes in the British landscape. They have a superficial resemblance to grasses, and are often ignored because they lack conspicuous flowers and can be annoying, intractable weeds in areas with damp climates, but when examined closely with a hand lens their flowers can be exquisite.

Close-up of a flower of the Baltic rush, Juncus balticus.

Photo © Chris Jeffree

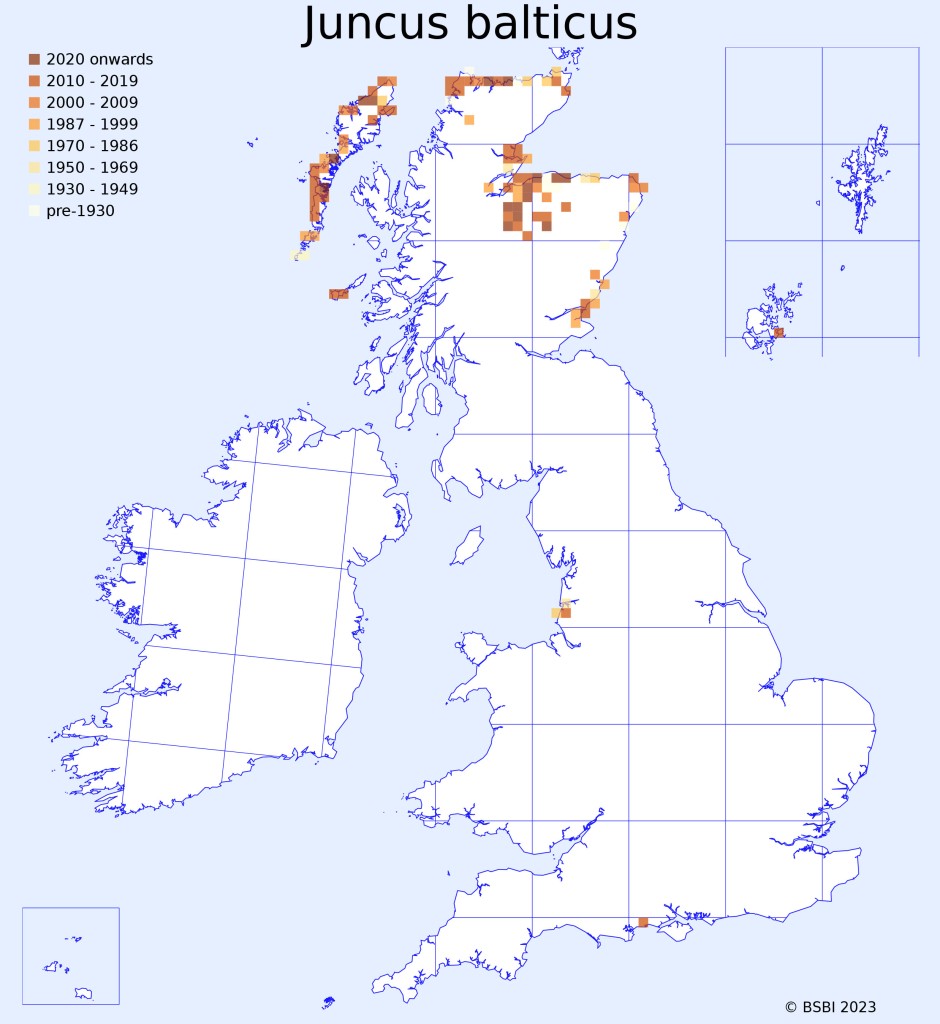

Juncus effusus L., the soft rush, Juncus conglomeratus L., the compact rush and J. inflexus L., the hard rush were named by Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum, 326 (1753), and to date, despite numerous challenges, their names have held. They are common upright, perennial, tufted rushes, and this tussock-forming growth form distinguishes them from the much less common Juncus balticus, Willd., the Baltic rush, which grows in long creeping rows, but is otherwise rather similar. All four have round, leafless, glabrous (hairless, without glands) stems, dotted with stomata, The inflorescence bursts, alien-like, apparently from the side of the stem. However, the pointed segment of stem above it is not a continuation of the stem but is technically a bract, a modified leaf. All of the other leaves are reduced to membranous basal sheaths. Juncus have open leaf-sheaths (see photo, left) while those of Luzula are closed.

Mixed stand of J. effusus and J. conglomeratus in a marshy hollow, Bathgate © Chris Jeffree

A stand of soft rush, Juncus effusus at Caulkerbush, Dumfries and Galloway © Chris Jeffree

| Juncus balticus ( above) forms extensive lines of stems while J. inflexus (right) forms dense clumps or tussocks. J. b. taken at Coul Links, J. i. at Maryhill, Glasgow. |

Photos © Chris Jeffree

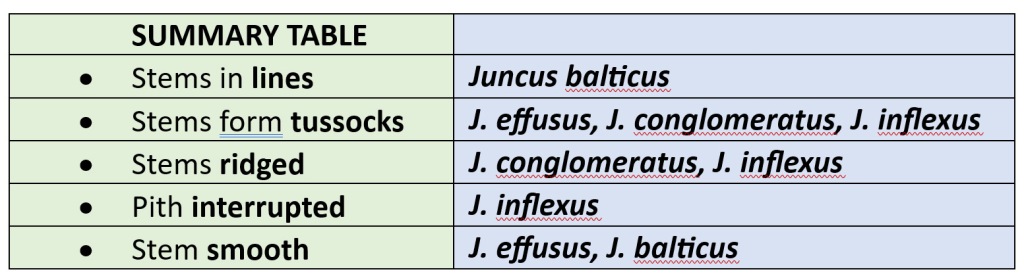

So, what are the differences between these four species?

First of all, the habit is a bit of a giveaway. Juncus balticus is creeping, the stems growing in extensive straight rows, while the other three species are tuft or clump-forming. The tussocks formed by hard rush Juncus inflexus, are greyish in appearance due to the dull glaucousness of the stems, and the clumps have an untidy appearance, because it retains the previous season’s stems. Its inflorescences have a looser appearance than those of J. effusus and J. conglomeratus. The stems are about 1.5mm in diameter, noticeably thinner than those of J. conglomeratus (2-3.5mm) or Juncus effusus, about 2.5 to 4mm.

In J. inflexus, like J. conglomeratus, the stems are ridged longitudinally – even without a lens you can feel this with a finger or thumbnail – and this character separates J. inflexus. and J. conglomeratus. from Juncus effusus which, like J. balticus, has a smooth, shiny, polished glabrous surface.

The compact inflorescence of Juncus conglomeratus, above left, and the looser inflorescence of J. effusus, above right. Note the dull, ridged texture of the stem of Juncus conglomeratus. © Chris Jeffree

Inflorescences and split stems of Juncus inflexus, above left, showing the ridged stem and interrupted pith and J. effusus, above right with continuous pith and smooth, brighter green stem. © Chris Jeffree

The pith is the clincher that separates J. inflexus from J. conglomeratus (both of which have ridged stems). Juncus inflexus has discontinuous pith, with gaps at approximately 1mm intervals. In the other three rushes discussed here the pith is continuous, and with care can be removed from the stem intact, to reveal a long thin cylinder of material that has various uses, of which more later.

All parts of Juncus inflexus are more slender than those of the other species. The inflorescence is lax. Last year’s dead stems are retained.

© Chris Jeffree

The inflorescence of J. balticus is sparser than that of J. effusus

and the stem smooth

© Chris Jeffree

Global Distribution

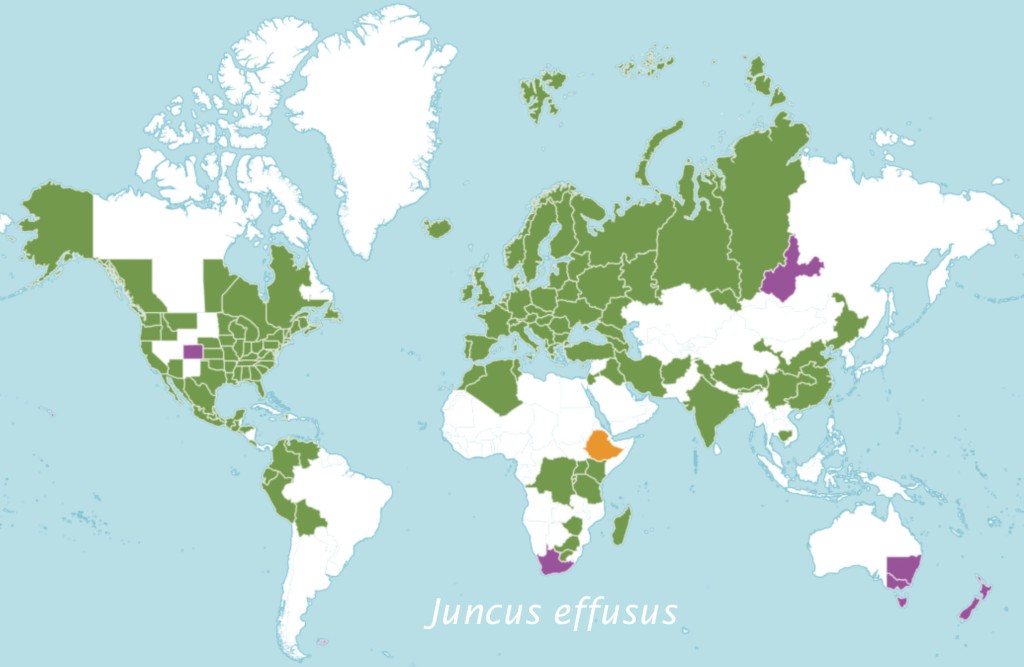

Juncus effusus and J. conglomeratus are listed among the amphiatlantic plants in Hultén’s 1958 publication, meaning that they occur on both sides of the North Atlantic, in eastern North America and in Western Europe, but are absent from the Pacific side of the globe. However, he expressed doubt about the few records in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and Connecticut, and Plants of the World appears to agree.

Global distributions of Juncus effusus (left) and Juncus conglomeratus (right) from Plants of the World Online. Key: Native (Green), Introduced (Purple) Uncertain (Orange)

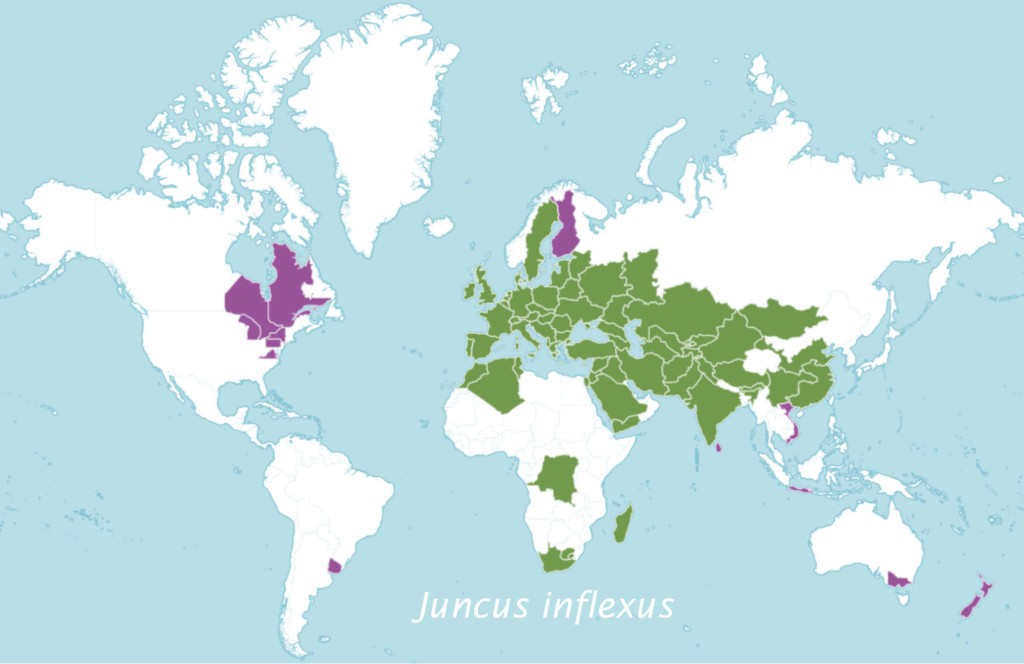

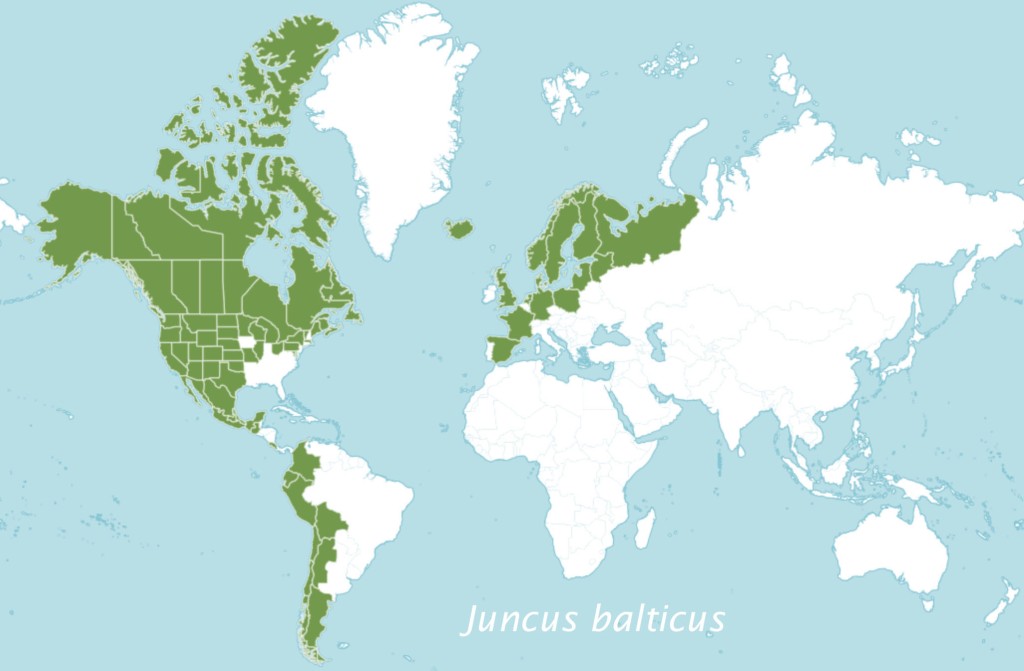

J. inflexus is native to western Europe. Hultén did not include J. balticus among the amphiatlantic plants, but it is nevertheless occurs as native throughout North America and the Atlantic and northern parts of Europe.

Global distributions of Juncus inflexus (left) and Juncus balticus (right) from Plants of the World Online. Key: Native (Green), Introduced (Purple)

Of the three species, Juncus effusus has the widest worldwide distribution. It is native in Europe, Asia, Africa, Madagascar, North and South America, and introduced to Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. It also occurs on far-flung oceanic islands including the Falkland Is., Hawaii, Marion-Prince Edward, St. Helena, Tasmania and Tristan da Cunha. Hultén (1958) commented “to which extent is natural or introduced is impossible to judge”. Juncus effusus has a separate, southerly stripe of distribution, from Turkey, through Iran and India to south-east China, and one might wonder whether it is really two or more species masquerading as one.

Juncus inflexus has a more modest native range, absent from the Americas, but nevertheless manages to span the entire Eurasian continent from Macaronesia to south-east China, preferring warmer southerly climates and avoiding the colder boreal and arctic zones. Juncus conglomeratus, like Juncus effusus, is made of sterner stuff, native from north Africa throughout Europe to eastern Asia, extending north to arctic Scandinavia, Svalbard and northern Russia including Novaya Zemlya.

Distribution in Britain and Ireland

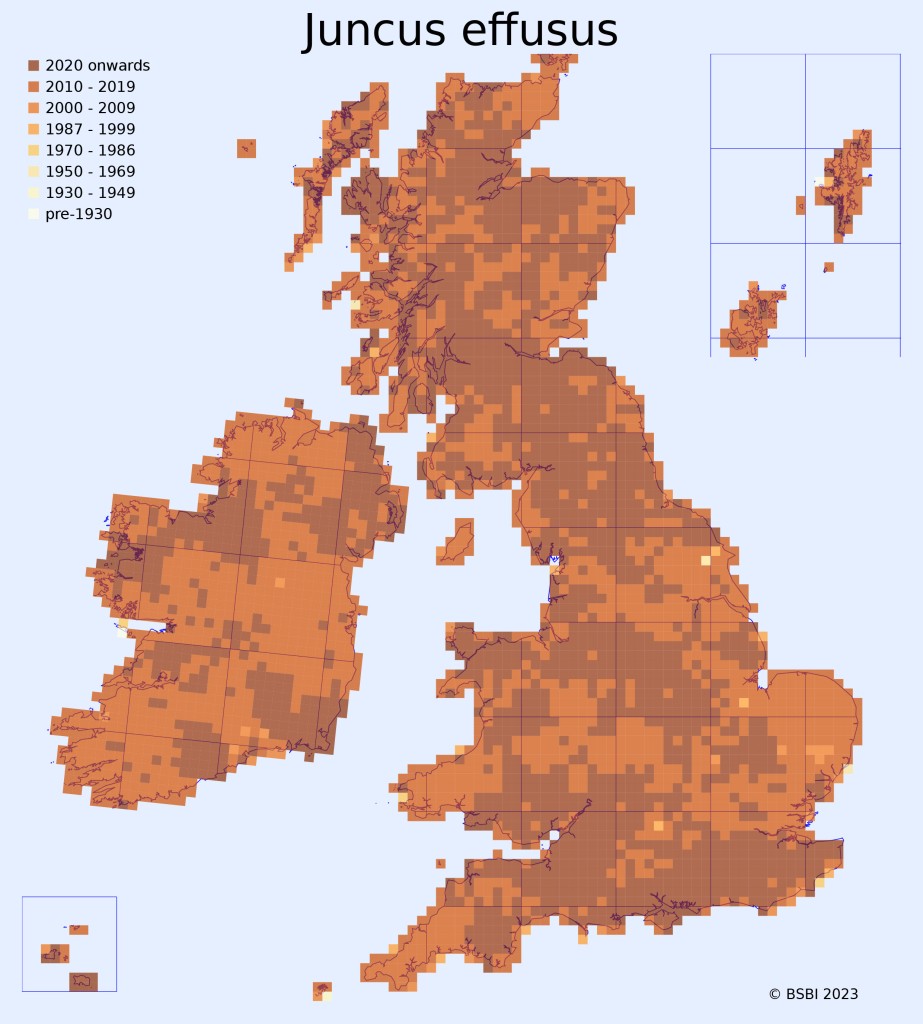

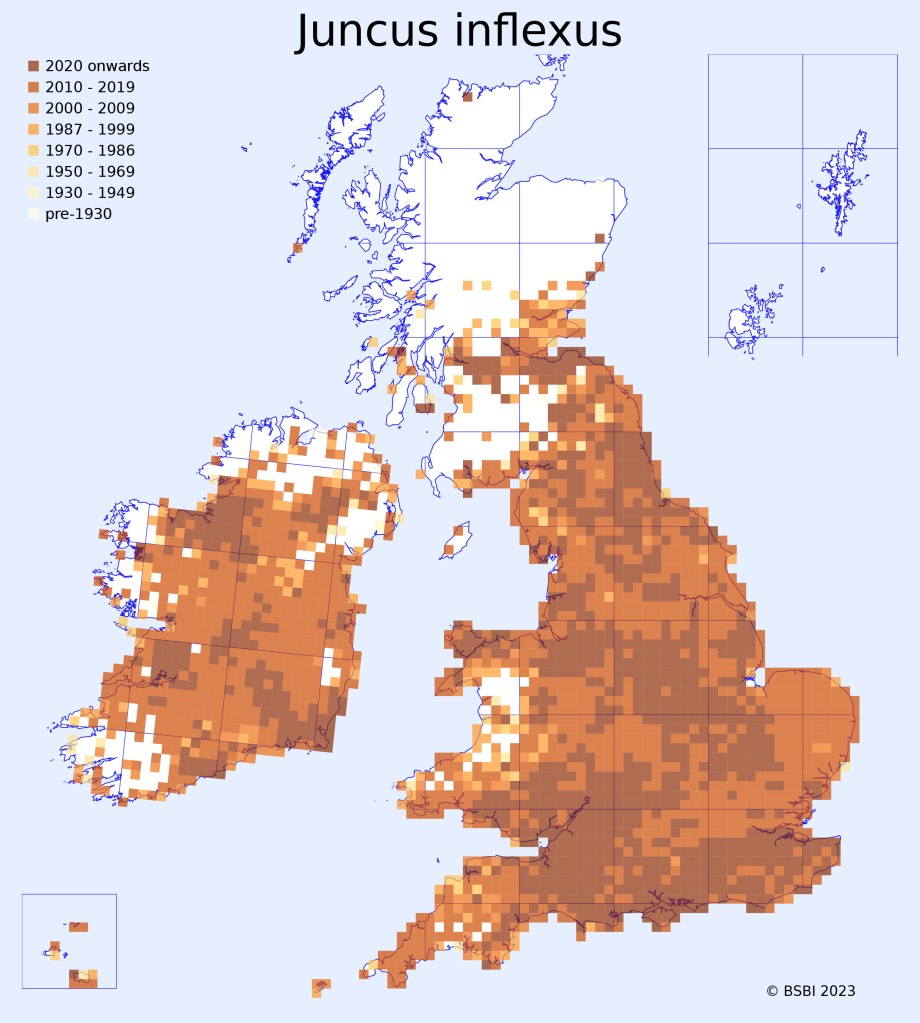

J. inflexus can co-occur in damp habitats with the other two, but much prefers base-rich soils. It is inhibited by acid soils in west Wales, north, west and southern Ireland and Galloway, and J. inflexus appears to have reached its northern / altitude limit north of the Highland boundary fault, a line roughly from Greenock to Stonehaven,

Juncus effusus and J. conglomeratus prefer acid soil. Nevertheless, they show little sign of this when mapped at 10km scale, since they are recorded in virtually all hectads of the British Isles.

Distributions of Juncus effusus (left) and Juncus conglomeratus (right) in Britain and Ireland © BSBI

Distributions of Juncus inflexus (left) and Juncus balticus (right) in Britain and Ireland © BSBI

Uses

The stems of rushes are long and tough, and for millennia have been used to weave all sorts of useful items. Rushes (J. effusus) are used to weave the rush mats beloved of student flats. They are also used in basketry and to form the woven seats of European chairs. Other species of rush sensu lato may also be used for the same purposes.

A split stem of Juncus effusus showing the continuous pith viewed from the side. Stem widths 3.5 mm.

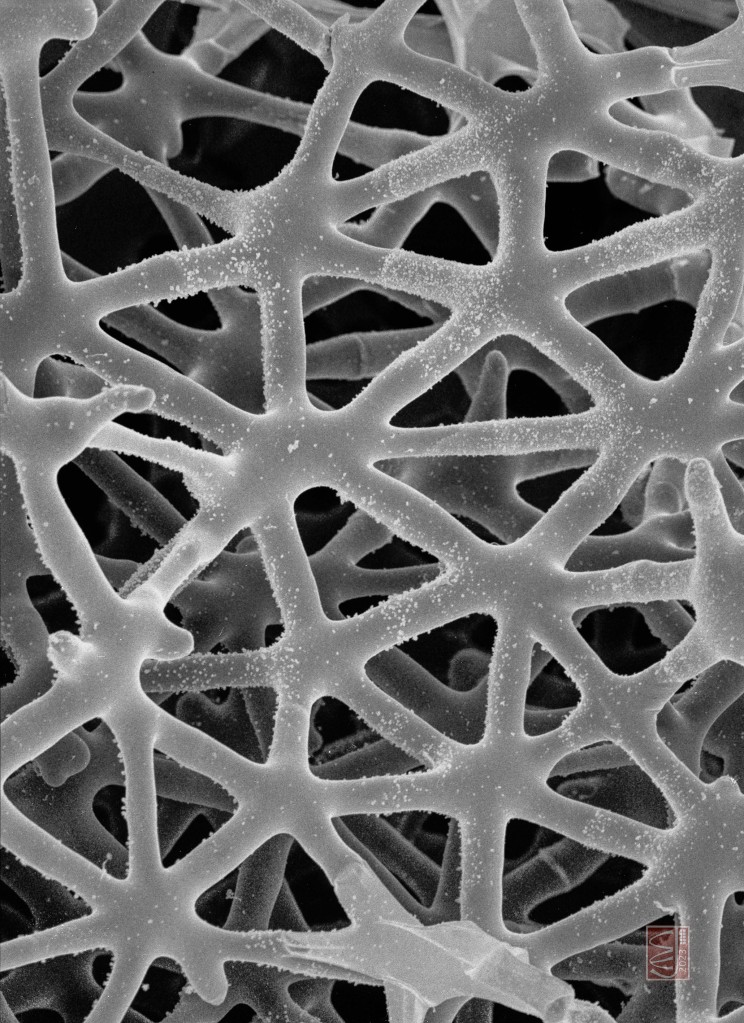

An SEM image of the pith of Juncus effusus, showing its porosity. The direction of view is along the leaf. Image width is ~0.2 mm.

Images © Chris Jeffree

Seen at high magnification (above, right), rush pith is an open mesh of star-shaped cells with very large intercellular spaces between, ideal for soaking up oil or melted fat.

Rush-lights were an early form of simple torch made from rush pith soaked in oil or fat. At its most basic, the rush light was a strip of rush pith, or several strips plaited together, laid in a shallow dish of oil. Fish oil, probably, but on St. Kilda they preferred the oil regurgitated from the stomach of a fulmar. Each to his own.

The continuous pith of soft rush, Juncus effusus, is best for these uses, and I am astonished to find that it is still obtainable online (e.g. eBay) for use in oil lamps.

Gertrude Jekyll (1904) gives a detailed description of the preparation and use of rush lights, including the apparatus used to hold the burning light (see picture) and the best sources of fat (mutton).

A selection of Victorian rush light holders. They are like small pliers, with one handle anchored in the base and the other forming a counterweight to keep the jaws closed. This arrangement makes for easy adjustment of the position of the rush light as it burns down.

from Gertrude Jekyll, 1904

Alternatively, the pith strip could be dipped repeatedly in melted fat, tallow or beeswax to build up a thicker layer of fat or wax to form a taper or a candle, with the rush pith used in place of a cotton candlewick.

In a small museum at Haddon Hall, Derbyshire there is a collection of 16th century English candles or rush torches. They consist of a bundle of stems of soft rush, Juncus effusus and hard rush, Juncus inflexus, bound together and coated on the outside with pine rosin or colophony, a by-product of the distillation of turpentine.

A 16th century torch made of rush stems bound with pine resin. ©Haddon Hall, Derbyshire

Analysing the rural economics of rush lights in “The Natural History of Selbourne”, Gilbert White (1860) calculated that 1 pound of rushes costing 1 shilling consisted of 1600 wicks with a burn time of about 30 minutes each. Doped with two shillings worth of mutton fat at 4d per pound, this would provide 800 hours of light for three shillings, about one week’s wages for a labourer.

REFERENCES

Juncus effusus L. and others – BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020, eds P.A. Stroh, T. A. Humphrey, R.J. Burkmar, O.L. Pescott, D.B. Roy, & K.J. Walker (2023) https://plantatlas2020.org/atlas/2cd4p9h.59w

Hultén, Eric (1958) The amphi-Atlantic plants and their phytogeographical connections. Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, 7, 1. Almqvist and Wiksell, Stockholm.

Jekyll, Gertrude (1904) Old west Surrey, some notes and memories. Longmans, Green & Co., pages 103-109

Linnaeus, C. (1753) Species Plantarum, 326

Plants of the World Online, published by RBG Kew, https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:442917-1

https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:443065-1

https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:442841-1

Stace, C. A. (2019). New Flora of the British Isles (4th ed.). C & M Floristics, Middlewood Green, Suffolk, U.K. ISBN 978-1-5272-2630-2.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rushlight

©Chris Jeffree, July 2023

One thought on “Plants of the Week, 10th July 2023 – Four Native Rushes (Juncus)”