I first saw this species growing as a weed in a potato patch in 2015. It’s common in parts of England but here in Scotland it is only ‘locally abundant’. Happily, my local Vice County Recorder was on hand that day and she had no difficulty in providing me with its name. She told me how the English name of the genus, Gallant Soldier, is a corruption of the Latin name, Galinsoga. I thought she must be joking but apparently it is a ‘well-known fact’.

The Shaggy Soldier Galinsoga quadriradiata, showing the flowers and their arrangement on the plant, and showing that the leaves are in opposite pairs. It is an annual plant, 20-60 cm tall. Photo: John Grace.

Since then, I’ve seen a lot of it. My lockdown walks in Edinburgh revealed it to be common in Leith and in the Edinburgh district of Polwarth where it lives happily on the thin soils of a traffic island and along road edges. In the Morningside district, where I live, it is under a town clock. I also saw it in China in 2019 and in the Czech Republic earlier this year. Evidently it is a great traveller. It may have ‘hitched lifts’ in batches of contaminated seeds, or simply stuck to the muddy boots and tyres of unsuspecting farmers, gardeners and council workers. Dogs’ feet too.

G. quadriradiata growing and flowering very well at a roadside, in accumulated debris (leaf litter and silt). Location: Polwarth, Edinburgh. Photo: John Grace.

The pretty flowers (less than 1 cm in diameter) appear in summer. The Local Authority workers here do spray these urban habitats with something nasty but this species escapes: either it has evolved resistance or its life cycle (which is later than most annuals) dodges the early spraying season.

G. quadriradiata, a single flower made up of many disk florets and five ray florets. Photo: John Grace.

It has a close relative, Gallant Soldier Galinsoga parviflora; that one is even more common in the world but less common in the British Isles. You can read more about it in a very entertaining blog elsewhere click. The Shaggy Soldier G. quadriradiata, as the name suggests, is quite hairy; its flower stalks are especially hairy, and the hairs are ‘glandular’ (each tipped with tiny secretory globe, which you may be able to see on the image below). The shaggy character of G. quadriradiata should be sufficient to distinguish this species from the other.

This image highlights the hairiness, and you can just see the glandular hairs. Photo: John Grace.

Galinsoga is a member of the Asteraceae, the daisy family. In the Americas it is sometimes known as the Peruvian Daisy. The ‘flower’ is made up of central disk florets and outer ray florets. The ray florets (3-5 of them, length of ligules a few mm) are white and notched, and the disk florets (15-30) are orange. Pollination is by insects, but failing that it is sometimes self-fertile. Seeds? I have read that a plant 8-9 weeks old can produce 3000 flower heads and up to 7500 seeds. The seeds can germinate immediately on warm moist soil so that in favourable regions 2-3 generations can occur in one year (but I don’t think it does that here in Scotland as it doesn’t germinate until the soil warms up properly; moreover, 3000 flowers heads per plant would be exceptional here).

Galinsoga parviflora was introduced from Peru into Kew Gardens in 1796, and at about the same time in Madrid and Paris. It escaped and spread throughout Europe. One early writer (1863) said that G. parviflora was ‘quite as common as groundsel’ in parts of London (but early writers were inclined to exaggerate). Gardeners and farmers in some warmer countries consider it to be an invasive weed but here in the UK it is not a problem – even in the balmy south of England it can be deal with by the stroke of a hoe whilst in Scotland both species are merely intriguing visitors.

Sir Edward Salisbury’s classic 1961 book Weeds and Aliens devotes a whole page to Galinsoga, showing an early map with appearance-dates for G. parviflora. which appeared in the wild much sooner than its shaggy relative. He says G. quadriradiata was first recorded as late as 1939. Salisbury’s name for G. quadriradiata was G. ciliata, the old name referring to the ‘cilia’, the points that can be seen on the ripe achenes at the end of the feathery pappus (just visible on the image below). Possibly the two species have sometimes been confused and so dates may not be true.

Mature detached achenes, showing the stiff bristles on the achene surface and the unusual pappus of hairs, each terminating in a fine point. Image: Wasp32, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In South American countries the young leaves are sometimes gathered and eaten, often in soup. Here in Britain people are quite squeamish about eating ‘weeds’ but perhaps that will change. Foraging is becoming a popular hobby, not with the poor and needy but with the middle and professional classes – because it is fun and slightly dangerous! The web site Plants for a Future (PFAF) says

“The leaves, stem and flowering shoots – raw or cooked and eaten as a potherb, or added to soups and stews. They can be dried and ground into a powder then used as a flavouring in soups etc. A bland but very acceptable food, it makes a fine salad either on its own or mixed with other leaves. The fresh juice can be mixed and drunk with tomato or vegetable juices”.

Left: as an allotment weed, G. quadriradiata invading a patch of young courgette plants (the plotholder doesn’t mind); right: an especially floriferous plant growing at an abandoned garden. Photos: John Grace.

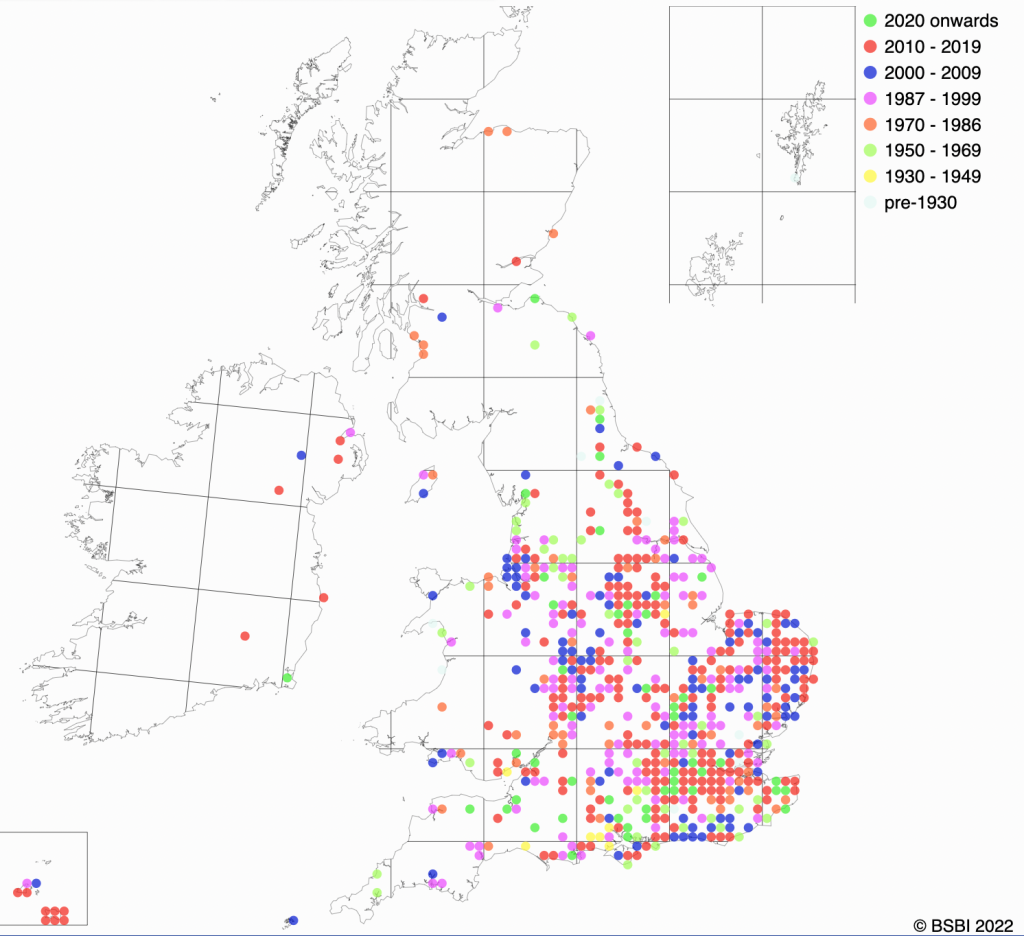

Although G. parviflora was recorded in Britain over a hundred years before G. quadriradiata, the maps below show that the latecomer has colonised our lands more effectively. This raises questions about the dispersal mechanism. I haven’t yet been able to compare the achenes of the two species. The suggestion has been made that the bristles on the achenes of G. quadriradiata enable it to cling to animal fur; perhaps this is an important difference between the two.

Perhaps it likes travelling by train. Brian Ballanger writes this in a recent Newsletter of the Dundee Naturalists:

“I was interested to see Galinsoga quadriradiata (Shaggy Soldier) on the platform of Stirling Station, unusual up here. It did appear by Dundee station a few years ago but I have not seen it there since”.

The similarity between the two distribution maps suggests that either the two species are very closely related and occupy essentially the same niche, or that mistakes have been made in identification. I was intrigued to learn that G. quadriradiata has 2n=32 chromosomes whilst G. parviflora has 2n=16. Chromosome doubling is a frequent mechanism for the formation of new species and so we may suppose that a plant of G. parviflora once doubled its chromosomes and formed the species G. quadriradiata. Hybrids between the two may sometimes occur but they are not known in the British Isles.

Distribution of the two Galinsoga species. Left: G. quadriradiata, right: G. parviflora. Data from BSBI maps.

For those people who want to see a summary of all research on this species, much more information is presented in a review article by Kabuce and Priede (2010) which you should be able to find here: click.

There has been much pharmacological research on Galinsoga, but mainly on G. parviflora. You can read one of the research papers here.

The genus Galinsoga is named after Ignacio Mariano Martinez de Galinsoga (1756- 1797). He was a famous physician in Spain’s royal court and is remembered most for writing a book about the health hazards of wearing corsets. His illustrious career is described here, but note that he was not a botanist.

References

Kabuce, N. and Priede, N. (2010). NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet –. – From: Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species – NOBANIS http://www.nobanis.org, Date of access 17/10/2022.

Salisbury EJ (1961) Weeds and Aliens. Collins, London.

©John Grace